Water crisis in Central Asia: Qosh-Tepa canal and shortage of hydropower

The capitals of the Central Asian countries are at risk of facing an irreversible water crisis, which experts Sobir Kurbanov and Eldaniz Huseynov in their recent analytical material compare with the situation in Tehran, where the emptying of reservoirs is already forcing the authorities to consider evacuation plans for part of the population. Although the region has not yet reached “Day Zero” (Cape Town scenario in South Africa), the trajectory towards a dangerous threshold is becoming obvious due to a combination of inefficient management, climatic stress and institutional weakness. Of particular concern in the current situation are two key factors that can radically change the balance of resources: the large-scale construction of the Qosh-Tepa irrigation canal in Afghanistan and the critical vulnerability of the hydropower sector in Central Asia against the background of climate change.

The regional hydro policy is undergoing rapid changes as Afghanistan accelerates the implementation of the Qosh-Tepa project. According to the Afghan authorities, the first phase of construction has been completed, and the excavation of the second phase has been completed by more than 90 percent. This suggests that the project may become fully functional by 2026 — two years earlier than the original deadline. The 285-kilometer-long canal is designed to divert from 6 to 10 cubic kilometers of water annually, which is about a third of the flow of the Amu Darya River, for irrigation of the northern regions of Afghanistan. The impact of this project has already ceased to be theoretical: in the Surkhandarya region of Uzbekistan, a sharp drop in the water level entering the Amu-Zang canal is recorded, which led to a reduction in the flow from 75 to 48 cubic meters per second and forced abandonment of vineyard cultivation in a number of areas.

The geopolitical consequences of the launch of the Qosh-Tepa channel in 2025 have expanded significantly. Turkmenistan faces the risk of losing up to 80 percent of its water intake, and Kazakhstan warns of a cascading effect. Astana fears that Uzbekistan, losing volumes of water from the Amu Darya, will be forced to compensate for the deficit by more intensive intake from the Syr Darya, which will potentially reduce Kazakhstan’s water supply by 30-40 percent. This transforms the issue of canal construction from a local dispute into a region-wide security crisis, making the creation of a framework agreement on cooperation with Kabul a strategic necessity.

The situation is complicated by the fact that the water shortage deals a direct blow to the energy security of the region, exposing the fragility of the water and energy balance. The winter of 2025 demonstrated a serious shortage of precipitation: national hydrometeorological centers reported that autumn and the beginning of winter were 40-70 percent drier than normal. For Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which depend on hydropower to generate more than 80 percent of electricity, this has become a serious challenge. Due to the shallowing of reservoirs, rural areas of Tajikistan faced severe restrictions on the supply of electricity, receiving light only two to three hours a day. The World Bank warns that this is not a temporary anomaly, but a new climatic reality: by 2035, river runoff may decrease by another 20-30 percent.

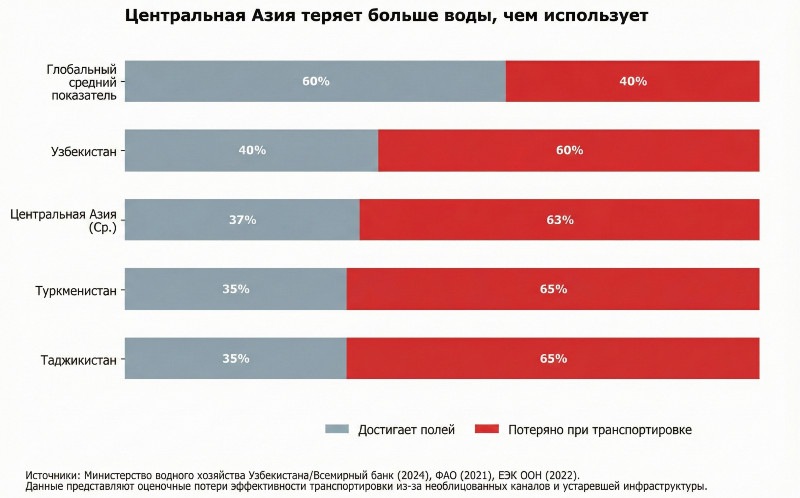

The problem is aggravated by the condition of the Pamir and Tien Shan glaciers, which feed the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. These mountain systems are warming significantly faster than the global average, and glaciers have already lost a significant portion of their mass since the 1960s. Despite the reduction of resources, the region continues to consume water with enormous inefficiency. Agriculture, which accounts for up to 90 percent of water intake, relies on outdated irrigation systems with open channels, where losses on filtration and evaporation reach 40 percent even before water reaches the fields.

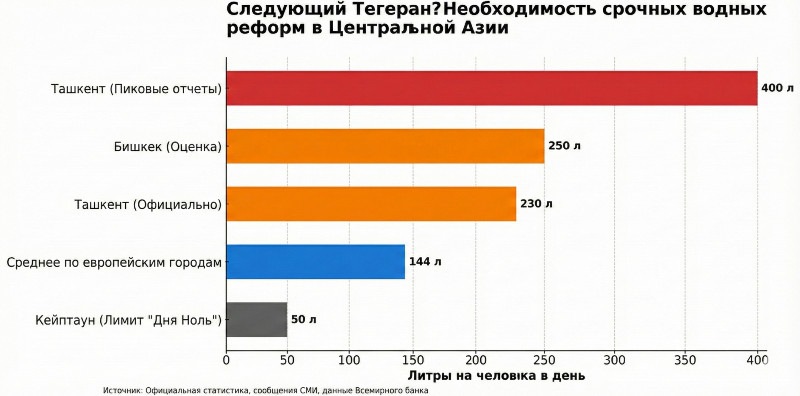

The city’s infrastructure is also in critical condition. Tashkent, Bishkek, Almaty, Astana and Dushanbe look more prosperous than they really are. A significant part of the water supply networks dates back to the Soviet era and is maintained through emergency repairs, rather than system replacement. Water losses in the networks reach 40-70 percent. At the same time, water consumption in the capitals of Central Asia is many times higher than in Western countries where sustainable development standards apply. For example, in Tashkent, peak consumption reaches 400 liters per person per day, while in European cities this figure averages 144 liters. Unrealistic tariffs that do not cover the cost of network maintenance and the lack of metering devices only exacerbate the problem.

Without decisive actions to modernize the infrastructure, introduce water-saving technologies (such as drip irrigation) and switch to alternative energy sources (sun, wind, biogas), the region risks facing large-scale destabilization. The reduction of rural incomes in the Fergana Valley and other vulnerable areas will accelerate climate migration to congested cities. Competition for water threatens to intensify long-standing tensions between upstream and downstream countries. To avoid the scenario of the “Tehran moment”, the Central Asian countries need not only to establish a structured dialogue with Afghanistan on managing the influence of the Qosh-Tepa channel, but also to radically revise domestic approaches to resource consumption.

Original (in Russian): Водный кризис в Центральной Азии: канал Кош-Тепа и дефицит гидроэнергии